Analysis of the Thermal Conductivity in Nano- and Mesostructured Polymer Systems

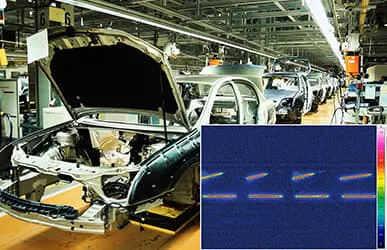

New materials with precisely controlled optical and thermal transport characteristics can make a large contribution to resource-saving thermal management. Scientists of the University of Bayreuth are pursuing this vision. They use infrared thermography to quantitatively determine thermal conductivity in nano- and mesostructured polymer materials.

Thermal conduction and thermal radiation are essential transport mechanisms that play a key role in various applications, from the smallest microchips to complete buildings. Their control requires a sophisticated material design that reaches into the nanometre range. Prof. Markus Retsch and his team from the Chair for Physical Chemistry 1 of the University of Bayreuth are working on the development and characterisation of such innovative materials. Modern cooling and air conditioning systems still require an external energy supply. But the cooling technology of the future should work without additional energy. To achieve this, materials are needed that selectively radiate heat. This can take place, for example, in clear weather when radiation occurs into very cold outer space through the so-called "Sky Window" in the long-wave spectral range of 8 … 13 µm, in which the atmosphere is transparent. "This process is called passive cooling," explains Prof. Retsch, "and requires materials that emit heat via thermal radiation within a selective spectral range. At the same time as little solar energy as possible should be absorbed from the sun, for instance by improving the reflection or scattering properties of the material."

InfraTec Solution

University of Bayreuth

Chair of Physical Chemistry

www.retsch.uni-bayreuth.de/en/

Thermographic system

VarioCAM® HD research 800

Thin Samples Actively Excited by a Laser

On the path to such passive cooling materials, understanding of the thermal conductivity process is important. To do this, Prof. Retsch's group is working with free-standing samples of, for example, thin polymer foils, 3D-prints, and fibre mats with a film thickness of only a few hundred micrometres. These samples are investigated with the goal of determining their direction-dependent thermal diffusivity. With this value and including the specific heat capacity and density of the sample, the corresponding thermal conductivity is calculated.

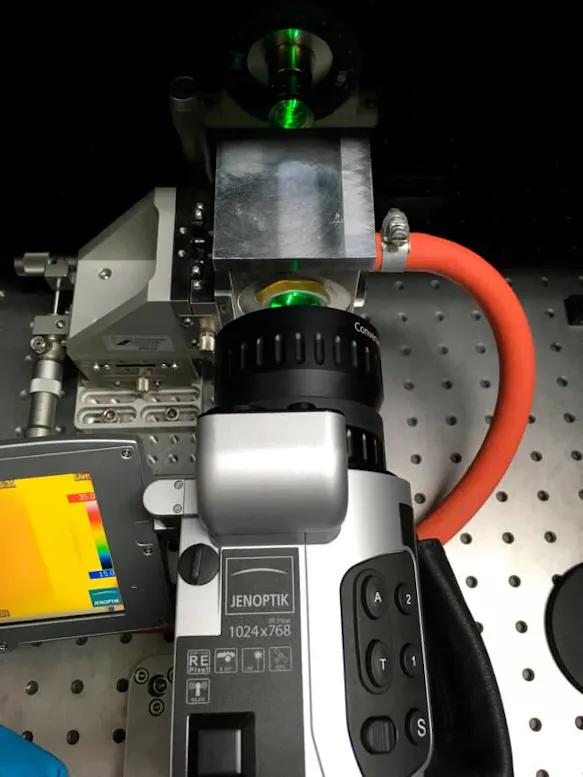

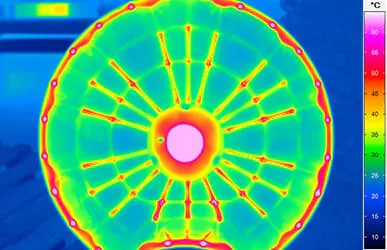

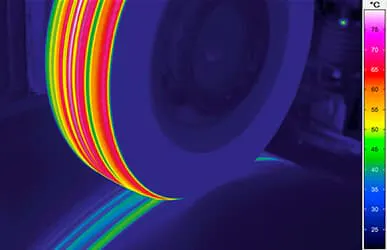

As part of the analysis, the measurement objects are excited by an intensity-modulated laser. Depending on the characteristics of the sample, the heat flux extends differently into the material (see fig. 1). The scientists actively control the entire measurement through the thermography software IRBIS® 3. The infrared camera that they use, VarioCAM® HD research 800 from InfraTec, detects the emitted infrared radiation, whose intensity varies with the lock-in modulation frequency.

Analysis Requires an Infrared Camera with High Spatial and Thermal Resolution

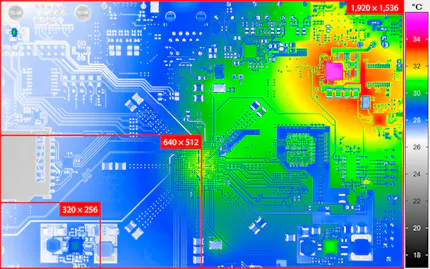

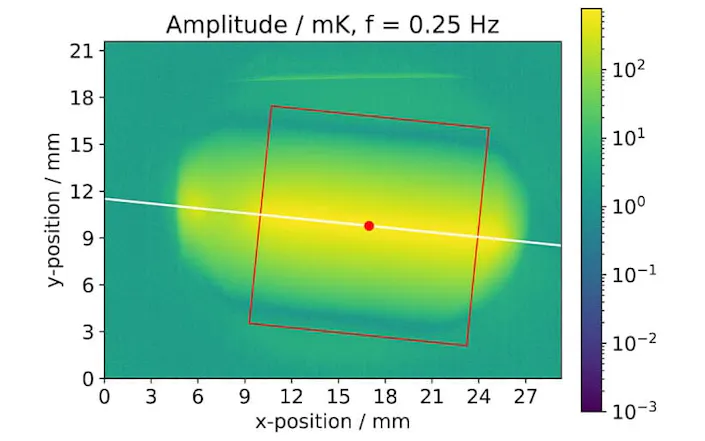

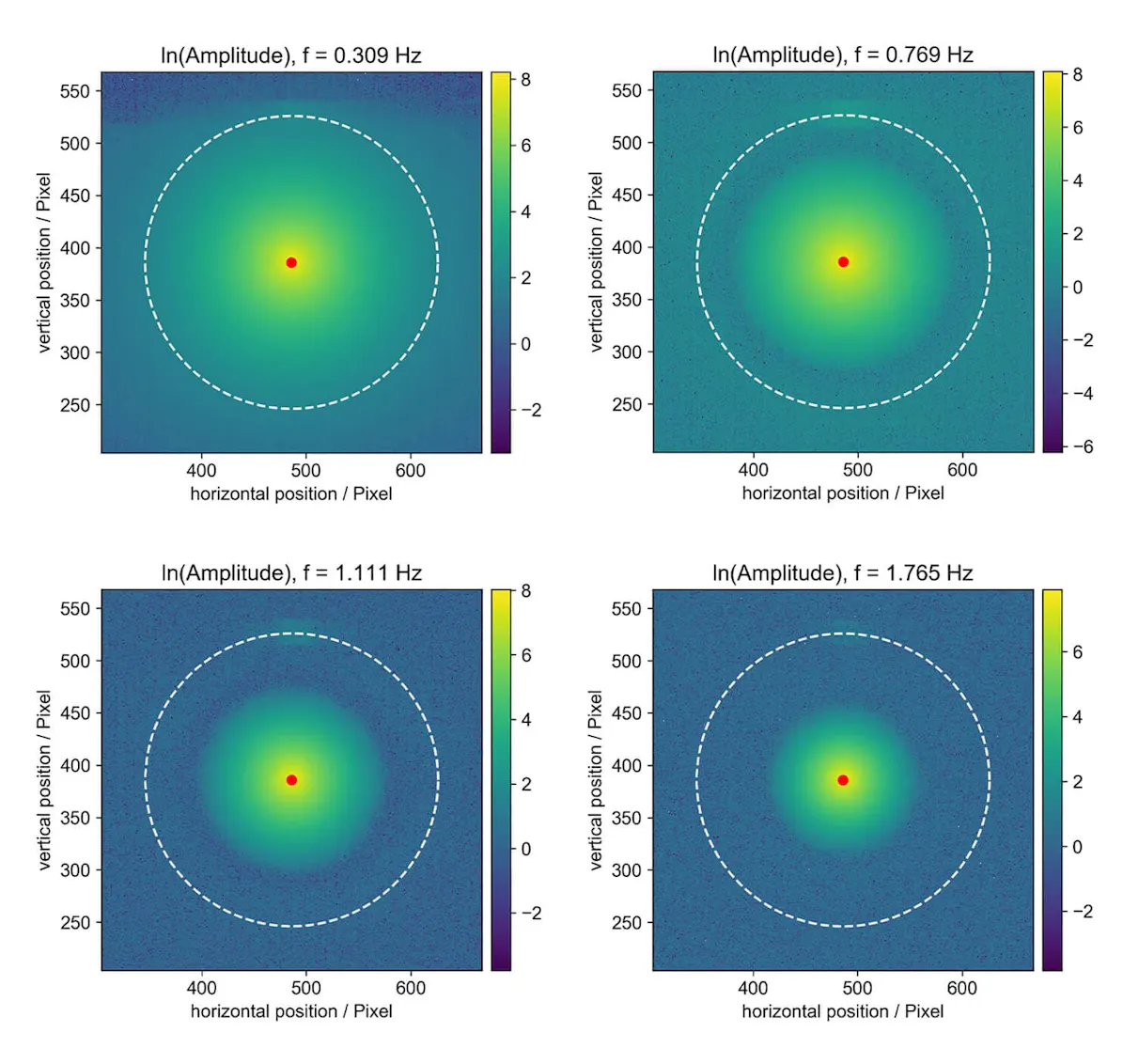

Of primary interest for the examinations are the position-dependent change of phase and amplitude of the emitted thermal wave. "In our case, the measurement method of lock-in thermography requires a detector format that is large enough to measure position-dependently on such small objects. Only then we are able to record the thermal wave precisely," says Prof. Markus Retsch. Therefore, he combines the detector format of the VarioCAM® HD research 800 of (1,024 × 768) IR pixels with an add-on close-up lens 0.5x for a 30 mm lens.

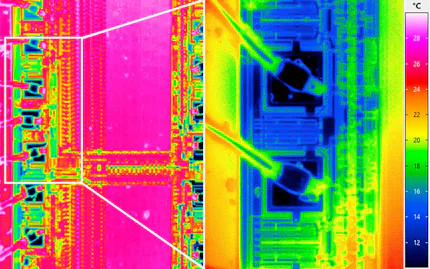

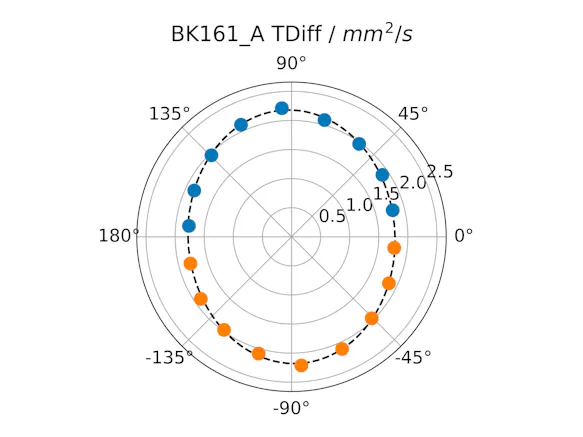

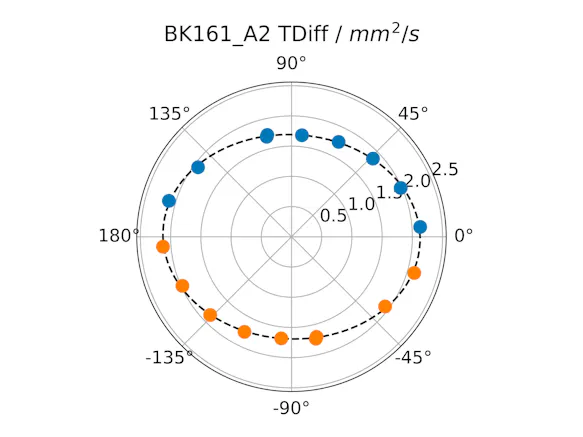

Fig. 2 Materials, such as Kapton foils, have an anisotropic thermal diffusivity. The dashed line represents the fit ellipse. Sample A2 is rotated by 90° relative to sample A. The anisotropy remains and is not a measurement artifact.

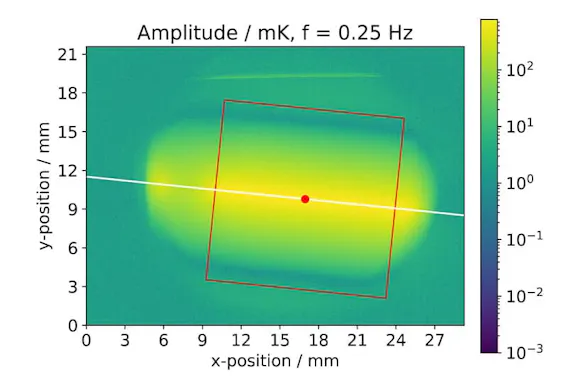

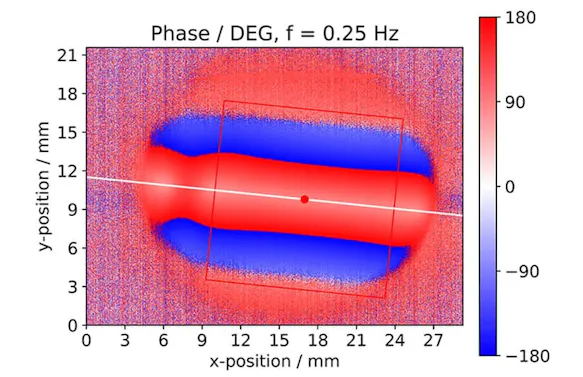

Fig. 3 Amplitude pattern (first) and phase pattern (second) show the temperature distribution on the surface of the Kapton foil. The foil is periodically heated on the back with a line-shaped laser. Amplitude and phase were calculated with the thermography software IRBIS® 3 active from InfraTec. A self-developed analysis software automatically finds the line laser (white line) and reduces the 2D-image data to a 1D-profile perpendicular to the laser line.

Fig. 4 The linearised amplitude pixels (left) and phase pixels (right) are depicted as a function of the distance from the laser line. From the slopes in the linear range, the scientists working with Prof. Markus Retsch determine the thermal diffusivity of the samples.

Besides the spatial resolution, the thermal resolution also plays a large role. Depending on the material, temperature-dependent phase transitions can occur, which negatively influence the measurement. Such errors can be avoided through measurement with small thermal excitations. But for that, a temperature resolution less than 100 mK is required.

Infrared Thermography without Alternative as an Examination Method

In general, the thermography system is part of an individually configured measurement environment. Prof. Retsch's group uses a self-developed vacuum chamber that permits the optical input of a laser. An IR-transparent window is installed opposite to the laser transparent port to measure the sample with the infrared camera. The technique of lock-in thermography can be easily combined with an infrared camera based on the microbolometer technology in this case. As the camera is a hand-held universal model, additional application opportunities for other tasks open up for Prof. Markus Retsch and his team.

Currently, nano- and mesostructured polymer systems are in the focus of various research projects. Furthermore, Prof. Retsch strives to expand the emerging research field of nanoscale thermal management and to provide new impulses for innovative cooling technologies. "With the flexible measurement environment, we can quantitatively determine the thermal conductivity along different directions of free-standing, thin films. This complementary information is important for a complete understanding of thermal transport in anisotropic samples. Only in this way we can reliably develop and improve new materials for use in passive cooling devices, for example." In particular, the thermal conductivity can hardly be assessed for such samples by any other method.